History

*This page is still under construction.

A History of Connections

The history of Kiln House and of the Keltneyburn Milton, which it is part of — and of the place where this is at, by the Keltney Burn, on the eastern edge of the Vale of Fortingall, at the beginning of Glen Lyon, together with what and where surrounds this location, is an involved and interconnected tale, radiating outwards and cross linked like a spiders web, each narrative involving people, places and events that connect, or overlap in strange and surprising ways.

Yet, while reason dictates that chance must be involved, there is an underlying logic to this in the geography of the landscape and its cumulative history, as evidenced by the numerous relics of antiquity it contains, encompassing stone circles, Iron Age hill forts, early Christian settlements, medieval homesteads; and high above the Keltney Burn, Garth Castle, the stronghold of Alexander Stewart, the Wolf of Badenoch (circa 1343 – 1405). This is where an ancient route across Scotland, passable on foot and with animals, from the sea lochs in the west, facing Ireland, intersects with a north south one; and since there are and have always been limited choices as to how the relatively impenetrable Highlands of Scotland may be traversed, due to the mountains, lochs and rivers to cross when doing so, in one way or another almost all of Scotland’s history has touched this place.

The Highland landscape has also helped shape its people and one in particular, David Stewart of Garth (1772 – 1829), whose statue is opposite Kiln House, a fairly uncommon thing to find in rural Scotland, played a pivotal role in significant parts of this story, including the reinvention of Scottish identity to become what it is today. Except how he connects to other people, places and events; and how the threads of history extend backwards and forwards in time from that too; and where they lead; and how often the environs of Keltneyburn feature in this complicated chronicle of Scotland; is equally amazing and almost never ending.

However, connections are not always random. People create them and so do the circumstances of history. Such being the case in this intricate story, it is told in parts.

And, regardless of wherever this tale truly begins and however far it extends, its telling has to start somewhere.

Part I

Keltneyburn Distillery

There are clues to the age and history of Kiln House in its roof design. A pyramid like shape that channels warm air upwards to a vent at the top is typical of crop drying buildings linked to brewing or distilling and occurs from the 18th century onwards, on the Malt Kilns of Maltings, Distilleries and, more often in conical form, on Oast Houses. This pattern continues to evolve throughout the 19th century to become the familiar pagoda style structure seen on many Scottish Distillery Malt Kilns built, or rebuilt, in the Victorian era.

The partial use of the original pyramidal version of this architectural form, at only one end of the Kiln House roof, is possibly because of the compact scale of the original Malt Kiln, however, perhaps also because of how it is built into the landscape, which places the kiln part of the building lower than — and therefore offset in relation to, the adjoining floors that would have been worked on as well in the malt production process taking place. These spaces next to the kiln, which might have had two shallow drying floors in it, seem too small for malting barley and might have been for loading and unloading the kiln, allowing the malt to rest and then screening it before grinding at the Keltneyburn Mill.

Corn drying kilns attached to early watermills are often quite rudimentary in comparison, which suggests something purposefully built in this instance. Consequently it is possible that Kiln House may be one of the earliest surviving examples of this style of Malt Kiln in the Scottish Highlands and is likely to be one of the few remaining from a small distillery of its type and age.*

The second notable feature is the roof vent, which for the function it performs and on a small building in a rural location that is part of an industrial hamlet, in a relatively remote place, seems unnecessarily elaborate, with an initially unexplained nod towards the grandeur of Regency style.** However, this makes complete sense once who builds it, why and when is understood.

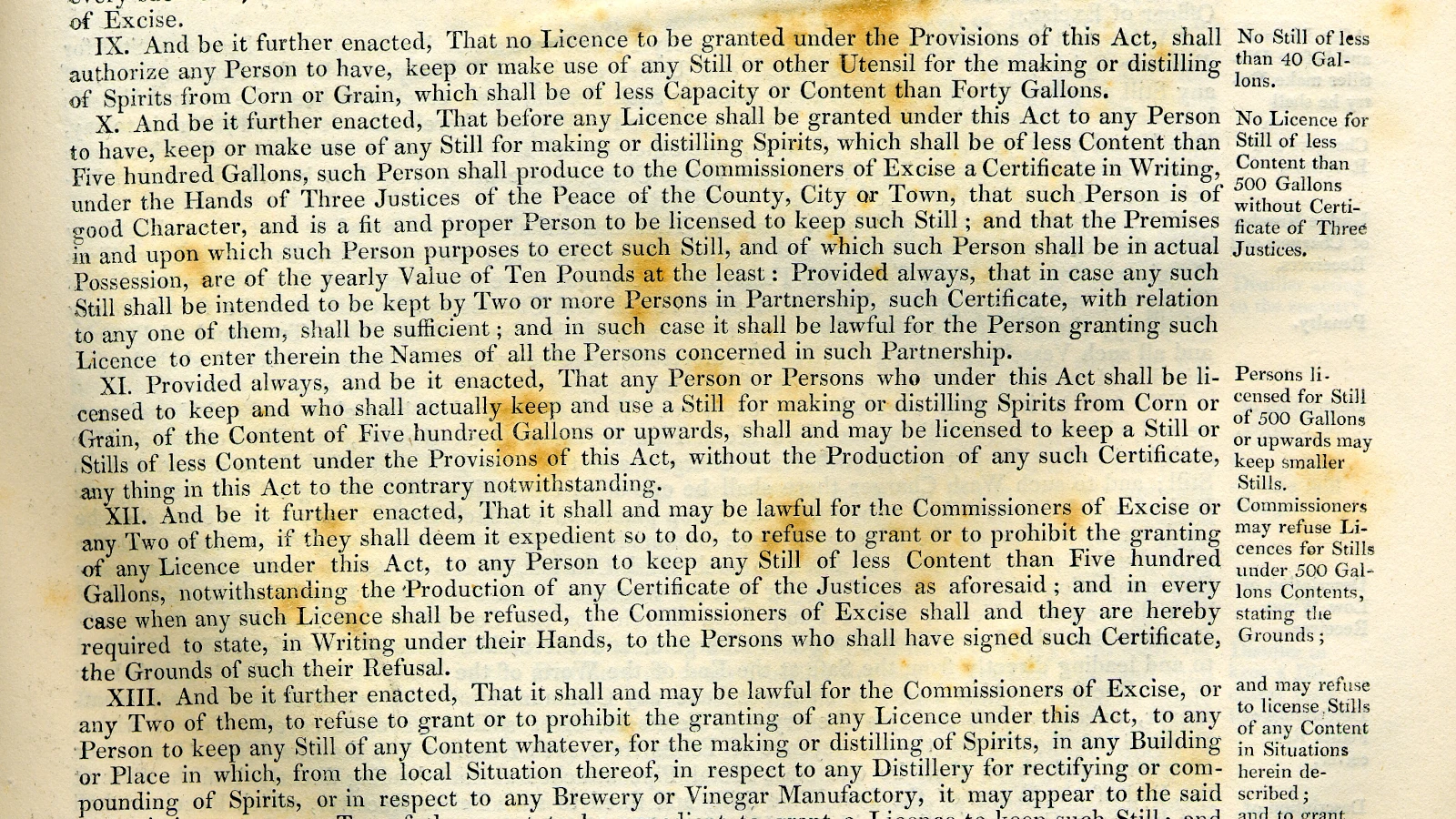

That was the then Colonel David Stewart of Garth. The distillery came into being because of a change in the law in 1823 that he may have had some involvement with or indirectly influenced. He certainly understood the issues and very likely knew those whose input had brought it about through mutual connection and direct acquaintance. This Act allowed smaller stills, of not less than 40 gallons, to be operated legally in the Highlands, which encouraged illicit ones to become legitimate, whilst making it possible for small scale distilleries to set up.

This solved a practical problem in production terms for the Highlands and was intended to resolve a messy tax situation that had arisen from the legislation of the previous century beginning with the introduction of a duty on malt in 1725. In the various Acts that followed a separation of distilleries above the Highland Line and an exemption for small stills for private use, had created more complications than intended. A boom in farm, or barn, based and other little distilleries followed the 1823 Act, which is generally regarded as having been the watershed that started the modern whisky industry.

David Stewart of Garth

Colonel David Stewart of Garth was a retired and well respected professional soldier who unexpectedly inherited the debt encumbered Garth Estate, including the Keltneyburn Milton, when his father and then older brother died. He was by then the author of a book, Sketches of the Character, Manners, and Present State of the Highlanders of Scotland, first published in 1822, shortly before he came into possession of Garth; and a prominent member of the Highland Society, which existed in both Edinburgh and London. This meant he knew the author Sir Walter Scott and was known to many other prominent Scottish persons of the time.

Scott’s novels had made a romanticised concept of the Highlander popular and he had been invited to dine with the Prince Regent, who was subsequently made Chief of the Highland Society of London. How this connection then unfolded in relation to the reforging of Scottish Identity when the Prince Regent became King George IV and how David Stewart of Garth was involved in that, is a tangential story related below. However, in this context it explains the absorption of Regency style, albeit in a modest way to make a statement building of the kiln — and a timely awareness of recent legislation that potentially impacted Scottish landowners.

The book was substantially a work on the history of the Highland regiments, begun at the request of the Commanding Officer of the 42nd, the Black Watch, in 1817, which had lost its records during incidents occurring in 1771 and 1794. However, it became much more than that as it was written, as David Stewart acknowledged in his preface:

A work thus undertaken, as it were by accident, and without any previous plan or design, one part of the subject naturally leading to the other...

It included the first ever published Map of the Clans and a knowledgeable and sympathetic commentary on the Highlanders as a people, their history, background and traditions, he being ‘himself a Highlander’ as was later observed. There are also some insightful and detailed thoughts on what was affecting the Highland way of life and economy at the time his book was written, including some about whisky production, in which he makes several pertinent remarks that perhaps anticipate the changes that happen soon afterwards.

A substantial part of the problem was the difference between Highland and Lowland whisky and how the taxation regime affected them differently:

By act of Parliament, the Highland district was marked out by a definite line, extending along the southern base of the Grampians, within which all distillation of spirits was prohibited from stills of less than 500 gallons.

This required a scale of operation that was impractical above the Highland Line where a low yield form of barley called bear was grown; farm land was limited in its availability and scope, whilst transport was difficult. None of this applied to the Lowlands, forcing the Highlanders into a difficult situation.

…subject as they are to the many drawbacks of uncertain climate, uneven surface, distance from market, and scarcity of fuel. Thus hardly any alternative remained but that of having recourse to illicit distillation…

However, the smaller Highland stills were of a different shape and involved a slower process, especially if peat or maybe dried heather provided the heat source, plus they always began with malt as a way of extracting the most sugar from the meagre form of barley, bear — and malting, in particular the Malt Kiln, could impart flavour from the Reek, the fumes from the kiln passing through the drying floors, usually involving peat although sometimes birch wood. Therefore the Highland whiskies were always a Malt Whisky with distinctive flavour, whereas the Lowland distillers had begun making Grain Whisky to avoid paying tax on malt and increase their production to meet the demand from urban markets.

Parliamentary investigations into this had produced the Report respecting the Scotch distillery duties. Ordered to be printed 11th June 1798 and Report respecting the distilleries in Scotland, &c. &c. Ordered to be printed 12th July 1799, which concluded that...

The Act of 1823 legitimised a trade that was to bring about the whisky boom of the late 19th century and shape the styles of whisky that are savoured today.

David Stewart of Garth's book was possibly reprinted again in 1822, before it had two further editions in his lifetime, in 1823 and 1825. He was made Major General in 1825 and appointed Governor of St Lucia in 1829 where he died of fever, aged 57.

The Malt Kiln

According to a marriage contract dated 1766, there was already a brewseat and maltbarn at Miln of Keltney, which means that some of the required components of a distillery were at Keltneyburn to begin with. This combination of buildings suggests a small brewery for the local estate incidentally. George III (or George II???) exchanged a similar one at Fearnan with the Duke of Atholl in 17???...

Regardless of which.....David Stewart of Garth was quick to take advantage of the scenario.

That he had the kiln built is confirmed in his correspondence:

In a letter that is maybe from 1823 or 1824 he says:

"The weather is now fine — when the mason has seen the Clunie Kiln he can judge better — Neil Macdonald does not understand the thing and would never do, except as a builder."

This implies that there might have been something new or different about this kiln, or at least not typical of what else existed in the area at the time, which would be consistent with the beginning of the 19th century when technical improvements were being made to Malt Kilns and others introduced during the 18th century were coming into wider use.***

The date is confirmed by two further letters, one written on the 17th of March 1824, saying:

Unluckily the snow is so deep on the ground that the Mason can do nothing or form an opinion about the kiln — as there is no appearance of an early change, he returns home today —…

Then another dated the 26th of March 1824, as follows:

Malloch will tell you what they have done about the kiln — should they be ready to begin building before the lime is ready, I can supply them — The young lime quarrier has no tools, and none can be got in this country — will you send up in the caravan three square shouls or spades —three oval ones and three pikes of different sizes —Levers and Boring irons will be required when farther advanced —I will get wheelbarrows etc. made immediately —An experienced quarrier to teach the others is much wanted, there is one at Gourdie well recommended by young Michie…

Confirmation that the kiln being built must be for a distillery is confirmed by an entry in Pigot & Co.'s New Commercial Directory of Scotland for 1825-6, where under Fortingall (actually written as Fortingal and meaning the extensive parish that includes Keltneyburn, not the village of Fortingall), under Tradesmen, etc. is listed: Stewart Col. David, distiller.

Further corroboration is in another letter dated the 21st of March 1827 concerning money owed by a tenant:

I had a letter from Jo Anderson Overblairish describing his loss of horses and cattle and other distresses, and begging that I may not press him for Rent until I go home — Send for him and speak to him privately, and say that he knows I have every disposition to favour him, but when he recollects that along with the Rent, he owes me £17 for the use of the Distillery with some smaller sums I fear that his difficulties will be too much for him — however, let him try another year, and see what he can do but he must exert himself to get money as I cannot get on without it.

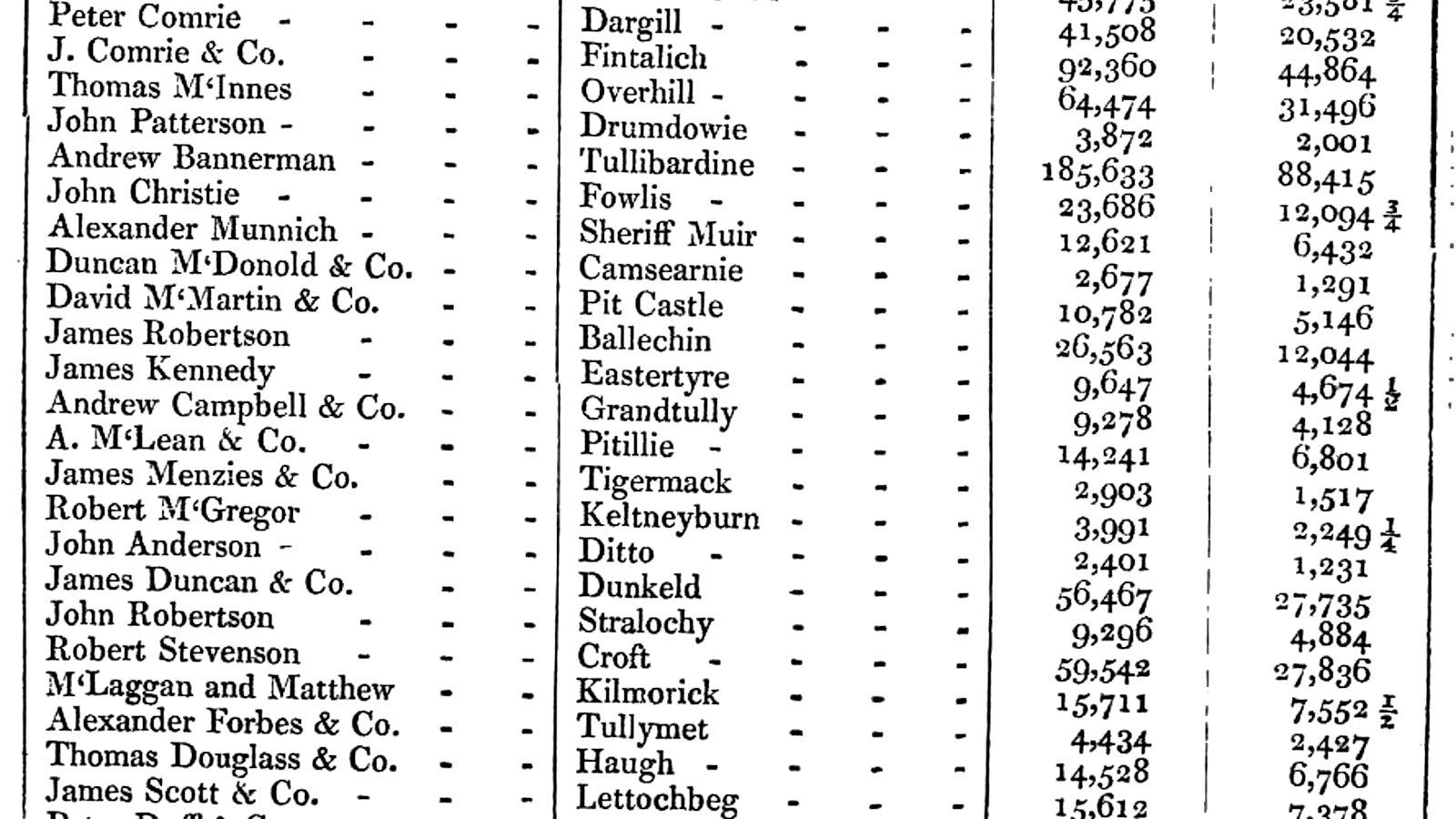

Firm proof is then found in the Accounts relative to Spirits, Malt and Distillery in Ireland and Scotland, 1823-26 printed for the House of Commons, dated the 4th of May 1827, where the Keltneyburn distillery is listed and evidently operational by 1825, with the same John Anderson named as its distiller having taken over from Robert M'Gregor. The list includes notable distillery names alongside Keltneyburn, such as Glenturret, that claims to be Scotland's oldest working distillery since 1763, along with many others that are now lost, or have since been more recently revived like Tullibardine. Notably though a number of names that claim historical provenance as far back as this are not present in these Accounts.

The Keltneyburn distillery disappears from the records after 1833, although its last proprietors were John Reid & Co. and then John Menzies & Co. that could conceivably have had connections to distillers that subsequently appear elsewhere. However, the local whisky story continues and resurfaces later in Aberfeldy. John Dewar was born in 1805 in the nearby hamlet of Dull, which lies between Keltneyburn and Camserney, which also appears in the 1823-1826 Accounts as Camsearnie. Therefore in 1828 when he left for Perth aged 23 he would certainly have known of them and of what these small Highland distilleries could bring to the future of the whisky market.

Early indications of this are found in the Report from the Select Committee on the malt drawback in spirits, 1831 where evidence was given concerning them echoing some of the comments in David Stewart of Garth's earlier book. ...

*****There needs to be some rearrangement of the content that is evolving to make better sense of it.

Map of the Clans

Map of the Clans 1822: Zoomable image ▸

Content goes here...

Clunie, shown at the top right of this detail of the Map of the Clans from his 1822 book, is probably the location of the kiln that David Stewart of Garth refers to in a letter, where he says:

"The weather is now fine — when the mason has seen the Clunie Kiln he can judge better — Neil Macdonald does not understand the thing and would never do, except as a builder."

Robert the Bruce

Another interesting feature of this detail is that above Garth Castle, which is shown at its approximate location alongside the Keltney Burn, the map marks the site of King Robert the Bruce's Cave, possibly corresponding to the location of Um Tam a Mhor (Uamh Tom A' Mhor-Fhir), sometimes translated as the Cave of the Great Man, on the southern slopes of Scheihallion. This is not entirely implausible. History has Robert the Bruce escaping after the Battle of Methven in 1306, towards the west, from which various theories and later narratives arise. However, Bruce's allies the Scottish Knights Neil Campbell, John of Strathbogie Earl of Atholl and Gilbert de la Hay would have known the surrounding areas better than the English forces and Atholl had lands to the north. The route to this remote location would have been fairly direct for those that knew of it and yet through uncharted, challenging, sparsely inhabited terrain for those that did not.

Robert the Bruce might also have know of this place. There is another association with the vicinity in that the Queen's View at Loch Tummel is thought to have been named after his first wife, Queen Isabella, not Queen Victoria as was later assumed.

Then again the upper reaches of the Keltney Burn are also known as Alt Art, Authur's Burn, supposedly after the legendary King Arthur, who is linked to Scotland through Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain) dating from around 1136, several place names and some historical facts that could actually be connected to the origins of the myth.

George IV, Sir Walter Scott and Tartan Tales

The Highland regiments were also heros of the Napoleonic Wars...

Also in 1822 George IV made his state visit to Scotland … The pageantry for this was orchestrated by Sir Walter Scott with Colonel David Stewart of Garth prominently involved both in the procession and reception; and behind the scenes as the go to authority on what the Clan tartans were supposed to be. George IV expected to see the Scotland that Sir Walter Scott wrote about and had an extravagant outfit made at enormous expense to wear during the visit, which included pink silk stocking to wear under his kilt, so that his Royal legs would not be exposed to common view.

… In fact the wearing of tartan had been outlawed for men in Scotland/the Highlands in 17?? after the Jacobite uprising of… and its continuation had been through the military version of Highland dress, as worn by the regiments, each of which had its own tartan… and in the flamboyant portraits of Scottish noblemen resident in Edinburgh and London. Whether there had been Clan tartans as such historically is debatable. There had been local and regional tartans and ones perhaps associated with some leading families, although not necessarily involving as strict a system of classification as suddenly arose. The Celtic Club had been collecting tartan patterns and documenting them, which had also involved David Stewart of Garth (?)… This is what George IV wanted to see, so Sir Walter Scott wrote a pamphlet on how to look Scottish and everybody dressed up.

The procession of the Highlanders was huge success and some of the present day concepts of Scottish Identity were accidentally reinvented as a consequence of all of this.

…two Welsh brothers went to see these events and a few years later resurfaced as the supposed Sobieski Stewarts, allegedly descendants of Bonny Prince Charlie’s sister(?) and they published a book about tartans, the …. , claimed to be based on a much older book that had been copied, although unsurprisingly they were never able to produce it. …despite being recognised as frauds by many they had tapped into a popular idea and several of the authentic Clan Tartans that persist have their provenance in these happenings.

…by the time of Queen Victoria’s visit in 1842 Clan Tartans and kilt wearing were firmly embedded in the popular perceptions of Scottishness and tartan style patterns in silks and other fabrics became fashionable for women’s dresses for a while.

Queen Victoria and Taymouth Castle

Content goes here...

Taymouth Castle

Content goes here...

Tweeds, Woolen Mill and Dyeworks

Content goes here...

Scottish Tourism

Content goes here...

A History of Connections

Logic of the Landscape

Ancient and Modern

Famous Footfall

Everything Happened Here

*Drying grain before milling it would often be a necessity in the Highlands of Scotland due to the prevailing climate. This is what a Corn Kiln does. A Malt Kiln stops the process of malting where the starch content of the grain, for a Scotch Malt Whisky usually barley, is converted into sugars. These are different purposes; however, Kiln House could have performed both these tasks. Contrastingly the Watermill in Aberfeldy has a substantial corn drying feature inbuilt, although is a later structure on a larger scale.

** There is only one other in the region that is similar, which is on the mill at Archarn… which is possibly slightly later and not obviously/historically linked to being, on a Malt Kiln, whilst … the vents at Camserny Mill and on the remains of the Dull distillery are basic and plain, with those on later larger scale distilleries not quite so elegant and more functional…

*** These include the channelling of hot air from the kiln through pipes, or the use of steam, to limit the direct exposure of the malt to the fumes of the fire, as well as ways of controlling the air flow and temperature, to make the production of pale or dark malts more predictable.

History &c.

Queen Mab

Queen Victoria &c.

Prince Albert

Taymouth Castle

Kenmore and Killin

Beach 3½ miles. Shop 3½ miles, pub and restaurant 2½ miles.

Quick brown foxes

The quick brown fox fixes flooding ffast fflippently and that's a fact!

*This page is still under construction.

- EPC Rating: E

- Scottish Short-term Let Licence: PK11053F

Content © Kiln House 2024